A biography of a special fish By June Allen February 17, 2003

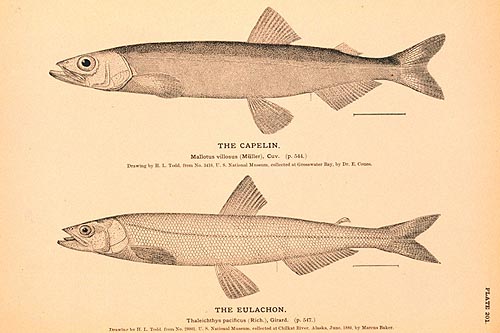

Bill Baker's gone now. Bert May, getting on in years, still fishes, but in his sleek new seiner Empress. Bert inherited his ooligan-harvest responsibility from his Tlingit great-grandfather Major. The Major family "owned" the ooligan fishery on the Unuk for countless generations, just as Tsimshian families to the south owned them on rivers in British Columbia and Tlingit families to the north owned theirs. Each year these days Bert's successors, his brothers Bo and Louie Wagner, make the ooligan run to the Unuk River. Louie's son now accompanies his dad and uncle for the fishery because the traditional ooligan mantle will fall on his shoulders in the future.  Photo courtesy University of Oregon And each year the tricky little ooligan arrive in Boroughs Bay singly but finally school only as they reach the mouth of the Unuk River or one of the nearby streams that empty into Behm Canal some 50 or so miles east of Ketchikan. There's little or nothing to announce their arrival until a sudden aerial convention of shrieking seagulls and soaring eagles notice the suddenly schooling fish! That's when the Wagners' nets are waiting! No one knows exactly when the valuable little fish will show up but when they do, it's a brief three-day fishery while the ooligan spawn. So it's heads up for the Wagners who check often for the ooligan appearance. Most years they get the fish, although occasionally they will be fooled by a too-early run, and, in 2002 ice conditions prevented them from netting the fish. The harvest is always so important! Native Alaskans in the whole region wait impatiently for the spring catch. Bert May, often coaxed to tell how he knew when the ooligan were due to arrive, always said, "When you see the first robin." Bo Wagner of Metlakatla once said, "It's the one time we know that every Native and a lot of non-Natives, too, will be feasting on the same thing at the same time - ooligan." The small silvery fish begin their annual journey somewhere above the Russian River north of San Francisco. They continue up the Northwest Coast and along the Inside Passage, shoaling at the mouths of good-sized rivers, and eventually end their journey in the Bering Sea. Missionary stories from the late 1800s say that the Stikine people called the fish szag and Chilkat people called the fish ssag. They were generically called "oilfish" or "candlefish." The fish are so rich in oil that a sliver of bark inserted into a dried ooligan will serve very well for a candle! The official name is eulachon,

and that's pronounced "OO-li-kan" and thus the common

name "ooligan" There are some, however, who insist

the name is "hooligan" and that's what they call the

fish. A rose by any other name and all that. But it's believed

that the mispronunciation is the result of a very popular early

1900s newspaper comic strip called Happy Hooligan. The main character

- a ne'er-do-well comic strip kid - is always in trouble. The

name Hooligan is said to be the surname of a rowdy, trouble-prone

Irish family. And that may be where the misnomer came from. Ooligan are part of the region's native legend and lore, and of their history, economy and even transportation infrastructure in years gone by. Bert May tells of his own experiences in learning about the fish. "Years ago when I first started fishing ooligan," says May, "I was so eager for the catch that I netted the first fish that came in on the high tide. When I brought them back to town, disappointed people would say, 'Where are the eggs?' I soon learned more about ooligan!"  Courtesy National Oceanic & Atmospheric Adminstration (NOAA), NOAA Central Library That initial influx of male ooligan is great for the oil. The egg-laden females that follow a day or two later are considered better for eating - not for oil, because the eggs get in the oil and "float around," May says. Local Natives say the Unuk River ooligan are superior to runs elsewhere because the fish are caught right at high water as they enter the river. In other locations along their Pacific Coast route they are harvested after the fish have run up miles of river and have used up much of their oil to survive the lengthy run. When Bert May was a boy, there was still his family's ooligan fish camp on the Unuk, with shacks and a huge cast iron pot for rendering the oil. It was an enormous kettle, he says, and looked like the "missionary" pots seen in cartoons of South Sea natives cooking missionaries. The kettle, in which each batch of fish was boiled for 12 hours was hung from chains attached to a tripod. No one knew even more than half a century ago how old that pot was or where it came from. May guesses it weighed 200 pounds or more. Then years ago the river moved back and the fish camp crumbled away. May last saw the pot used as a decoration in front of a hunting lodge on the river. Bo Wagner says it's gone now. May says, "I didn't care about anything like that, like the pot, when I was younger. Now I wonder what happened to it and wish I had it back." He thinks the last one to use the pot for rendering was Henry Denny, maybe back in the 1940s. The rendered oil was brought back to town in those square five-gallon Hills Bros. coffee cans, he remembers. May explains that in the early years his grandfather "owned" the Unuk River fishery. One great-uncle, he says, owned the Chickamin ooligan fishery and another uncle the one on Boca de Quadra. They were all from Cape Fox Village and had winter homes there as well as at Loring. May adds, "I don't know why they had two winter homes or when they chose to live at one or the other. I do know that this ownership of the fish streams was respected by everyone then. If someone else needed fish, they came and asked for them, and my great-grandfather or great-uncles would make the catch and those who needed fish got them, free of charge. With the harvests of ooligan they netted, my ancestors would sail all over the region, clear around Prince of Wales Island, and trade for things they needed - maybe harvested seaweed or dried halibut, whatever. It was the barter system." These days the Wagner brothers charge a nominal fee for the fish they net and bring back to Ketchikan, low enough that anyone can afford them. Mostly the fish are sold in 10-lb. bags. The ooligan also meant something else important to earlier Native generations. The nutritious little fish could mean the difference between starvation and survival. By the time "the first robin arrived," winter supplies could be short or even exhausted. In a lean year, the ooligan were literally lifesavers. All up and down the coastline, the people gathered to trade in the fishery. To the south, the Haidas from the Queen Charlotte Islands arrived at the Nass in their big, elegant canoes, ready to trade. Others from Tsimshian tribes farther inland came to the coast. The Dene Indians of the interior arrived by the same routes, called the Grease Trail, all coming to trade for the fish and oil. The same was true for those heading for the Unuk to trade. They came from the north and from inland locations along traditional trails, called grease trails. A decade or so ago the Alaska Department of Fish & Game felt some concern about the viability of the ooligan resource and considered limiting or possible closing the Unuk ooligan fishery. Present property owners along the Unuk said there seemed to be fewer fish than in the past. And there were years when the usual spawning grounds showed lesser numbers. Bert May, however, explains that the past few decades have been warmer than usual and because of that the Unuk has been muddier than the fish like. "Ooligan want clear water for spawning, he says. "In that case, the fish go up the Klahini, a tributary of the Unuk, or into the Chickamin." And that's why the numbers appear to be smaller. Then in 2000 the traditional rights of the Native Alaskan fishery were recognized and the ooligan harvest continues as it has for generations past. There is no great pulsing market for ooligan in local grocery stores and you won't see them there, but you never know try 'em; you might find you like 'em! Just remember that they're best cooked hot and fast, the head, tails and innards intact. Ooligan arrive even earlier than the first tourists! So watch for that first robin and "think ooligan, think spring." And, does anybody know whatever happened to that humongous big rendering kettle? It should be displayed with pride and honor as part of the tradition of the awesome little fish formally named eulachon.

Historical Photographs:

All rights reserved. Not to be reprinted in any form without the written permission of June Allen.

|