but big in history By June Allen March 03, 2004

Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress). Gift; Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington; 1951. Courtesy Library of Congress

One of the town's historical bows to renown is that in 1851 a Russian trading post at Nulato was the site of a bloody massacre by neighboring Koyokuk Indians, who according to some stories - slaughtered everyone in the village, Indian and white. In several accounts of the attack, the victims included the Russian trader as well as 13 members of a visiting British search party who had followed the Yukon River to Nulato hoping to hear word of a famous English explorer who had gone missing several years before. When the marauding Koyokuks left Nulato, only two little children had managed to survive. Half a century later they told their stories to avid listeners. Then in 1884 Catholic Archbishop Charles John Seghers, now honored with the term The Apostle of Alaska, was murdered just a few miles short of Nulato. He had been fighting through early winter storms on his way toward the village to serve the people whose population and spirits had been devastated by a deadly measles epidemic just three years earlier. The priest was shot dead by his gone-insane traveling companion as the two neared the village.  .Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress). Gift; Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington; 1951. Courtesy Library of Congress

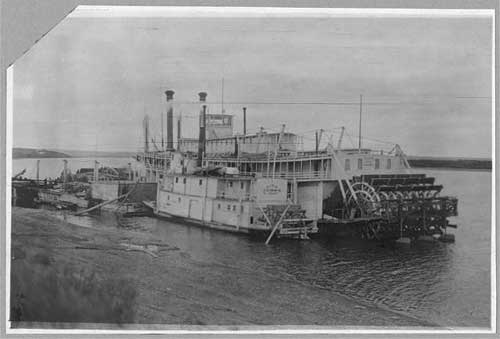

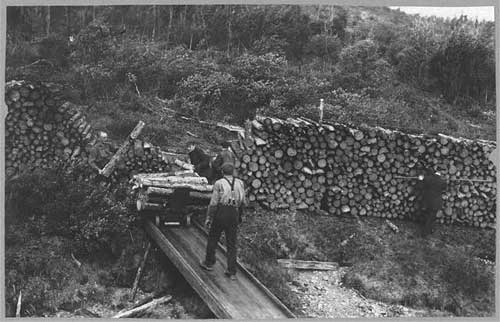

The ninety or so families in today's Nulato have radio and TV, their school has computers, swimming pool and a library. The plumbing in the village is rudimentary but they have a town washeteria. Their homes are heated largely with wood, although some public buildings are heated with oil. The people of Nulato have no taxis or car rentals but they have half a dozen air carriers at their service! Two centuries ago their transportation was by dogsleds in the winter and from late May to the first of October via the Yukon River, Alaska's once-great transportation corridor. It's hard now to comprehend the volume of traffic that coursed up and down Alaska's coastlines and the Yukon River in the early 20th century! Records show that by 1900, during the peak of the Alaska Gold Rush, there were 46 boats in operation on the Yukon! Two steamers a day would stop at Nulato to buy firewood for their boilers. The town's new post office, opened in 1897, was a popular stop en route up or downriver. The mighty Yukon reaches the Bering Sea as a broad, braided twist of uncertain channels moseying through its marshy flatland delta. It was no place for larger, deep-hulled river vessels to navigate. So travelers arriving in Alaska via the Bering Sea sailed northward some distance and came ashore at the Yup'ik Eskimo village of St. Michael on Norton Sound, then trekked eastward overland to catch a river boat at one of the deeper-water landings along the river, like Nulato. A Russian fur trader named Malakov reportedly arrived in the fish camp town of Nulato as far back as 1839 and saw the trading potential of the little village. He saw the coastal Eskimos come to this Indian town, offering seal and whale oil, tobacco and copper spearheads in trade. Malakov noticed that the spearheads bore the imprint of a forge in Irkutsk, which the visiting Eskimos must have received during barter with Chukchi Natives. The Nulato Indians also welcomed the new trade with Malakov and he traveled back out to St. Michael with 350 beaver pelts.  .Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress). Gift; Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington; 1951. Courtesy Library of Congress

The Nulato massacre happened on a dark Sunday, Feb. 16, 1851, when fires were lighted for a traditional Nulato potlatch. Weaving the varied but sketchy details into the story from a number of sources, it seems that a party of the villagers had gone north to hunt moose and would be gone for several days, leaving the village with fewer men than usual. But preparations continued under way for the traditional potlatch ceremonies. There were unusual visitors in town as well, staying for the night with trader Darabin at the trading post. They reportedly were twelve seamen led by a British naval officer, a Lt. Barnard, of the vessel HMS Enterprise, commanded by Capt. Richard Collinson. The ship was waiting for them at St. Michael. The men had come upriver on a search mission, hoping to find word of the fate of any survivors of famous explorer Sir John Franklin's lost expedition of 1845-47. Natives reportedly had told the visiting British ship of strange white men seen just upriver, possibly at Nulato. The British guests were disappointed to learn from the Russian trader that the "sighting" was apparently just rumor. So they accepted the trader's hospitality before setting out on the cold journey back to their ship. The men were probably talking together inside the trading post, enjoying the heat of the fire and a hot beverage, when smoke began belching into the room. A marauding band of Koyokuk Indians from farther upriver, said to be led by a fanatical shaman, had stuffed bundles of grass in the trading post's chimney to smoke out the trader and his guests. Soon the acrid smoke was blinding and choking the men who bolted for the door, only to find bedlam in the village. The Russian trader was killed with an arrow. Some sources say the British seamen - or some of them were able to escape back to their ship. Other sources say they were all picked off by arrows as they fled the smoke-filled log building, and died with the rest of the people of Nulato. Trade goods were stolen and fire later set to the entire village.  .Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress). Gift; Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington; 1951. Courtesy Library of Congress

The returning moose hunting party must have found unspeakable horror in their village. The location of the massacre is below today's newer Nulato and is said to be simply a curious grassy mound. The village gradually regained population, although it suffered, along with other Native Alaskan villages, through a killing epidemic of measles in 1900, the deadly flu epidemic of 1918, and the equally devastating tuberculosis epidemics into the 1950s that killed so many Alaska Natives and whites alike. Tragedy did not end with the 1851 massacre, however. Bad luck dogged Nulato for years to come. Census figures for 1880 counted 169 residents in the village. And then a significant gold rush in the area in 1884 increased the population. To serve the region, the Catholic church was sending missionaries to organize schools for the Yukon villages. A priest named Father Charles John Seghers was among the missionaries who traveled from village to village. His heart led him to Nulato in 1877 where he recognized the potential of the community's location. He hoped to build a central mission there. A year later he sailed south in an effort to raise church support for a permanent central mission and school to be built at Nulato. He was surprised to learn on his arrival in Vancouver, B.C., that he had been appointed as Archbishop of Oregon City, the posting to begin in 1880. He bowed to the will of God and postponed his mission plans, but he petitioned the Pope to be allowed to return to Alaska and his missionary post! His petition was granted. In 1886 he set sail for Dyea at the head of Lynn Canal, where he and his traveling companion, a hired man named Charles Fuller, would scale the Chilkoot Pass and, once reaching the Yukon, they would canoe downriver to Nulato. The approaching winter, however, set in early and hard that year. Miles before their destination the Yukon began to freeze, making progress tedious. The priest's cheerful good spirits and pleasure in nearing Nulato in spite of the hardships apparently wore on his companion's nerves. It was an arduous trip and Fuller gradually lost his mind, literally.  [between ca. 1900 and ca. 1930 Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress). Gift; Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington; 1951. Courtesy Library of Congress

Father Seghers' body was later exhumed and taken to Victoria B.C. where it lies now in St. Andrew's Cathedral. Father Seghers has been honored by being known today as The Apostle of Alaska. The mission school he envisioned was built in Nulato the year after his death. It was named Our Lady of the Snows. Although much has changed in the vast reaches of Alaska, many things change very little. Time in remote Alaska is measured by seasons and daylight rather than by the clock. Distance is measured by the calendar rather than the mile. Space in Alaska is so vast it requires no modifiers. And value and importance are in personal reckoning. One such item of importance: Nulato lays claim to the fact that the second raising of the Stars and Stripes in Alaska - after the flag of the United States was raised on the flagpole at Sitka on Oct. 18, 1867 - was at Nulato! The little village now has telephones and computers. But it also has retained the tradition of the Stick Dance, considered the most honorable and remarkable of the Athabaskan Indian culture, practiced in Alaska and among tribes in the Southwestern United States. The event rotates each March between Nulato and neighboring Kaltag, a dance honoring the departed and helping families deal with the grief and loss of loved ones. A decorated spruce stick is used during the dance and potlatch. It symbolizes the souls of the deceased - a final farewell to a loved one and the cleansing relief of closure. Nulato has had much experience with loss and grief, a remarkable community. And it was just 16 years later that the American Stars and Stripes were raised, at Nulato, after receiving word of the transfer ceremonies at Sitka on Oct. 18, 1867 - the second flag to go up in the new U.S. possession.

june@sitnews.org

All rights reserved. Not to be reprinted in any form without the written permission of June Allen.

|

|||||||