by Sid Morris USCG, July 1951 -July 1954 First Published: 1965

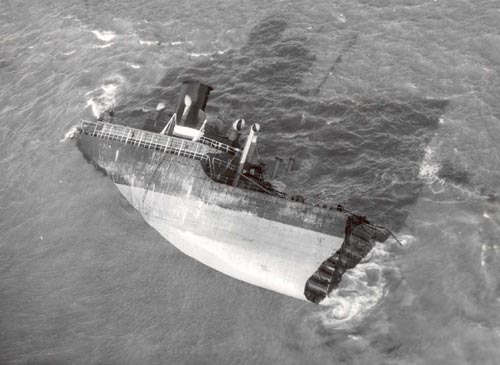

I looked up sharply from my "soggy" bucket duties and excitedly repeated the bosun mate's surprise announcement. "Not a ship, Morris . . . two of 'em, two tankers within forty miles of each other, cracked amidships off Cape Cod in last night's storm, and are in danger of sinking. The survivors are still aboard. Five or six seamen vanished when they split. I just got the word that we're on standby-alert." What about our 'availability repair' status? I heard the 'snipes' have already turn down one engine, and most of our 'deck apes' are ashore on 48 hour liberties." "We'll know soon enough," answered Blackie, our 1st class bo's'n, a sailor's sailor, who could make a 14" hawser stand up and perform tricks. "Two weather patrol cutters are at the scene now, but I bet the District Office (Boston) will order us to get underway before noon." "Oh, those dainty, white cutters will soon call for our assistance, they always do," I replied knowingly.  Photo Courtesy USCG (Official Coast Guard photograph) And so ran the vein of scuttlebutt aboard the broad-beamed, black and grey sea-going tug, CCC ACUSHNET (WAT-167), that frigid, snow-packed morning of 18 February 1952. The snow emerged violently from the cloud-bulged skies the morning before, but since this was February in Portland, Maine, I had come to regard the message of nature as a regularly scheduled event. The icy, biting wind swept in at noon and by dusk, their velocity had built up to 35 knots. That night the big black ship surged and rolled at the end of Maine State Pier as if she were bucking thirty foot swells. At 2200, the Officer of the Day piped the duty deck force topside to secure 12 inch manila storm lines to all clock-side bollards. The dawn greeted us with a ubiquitous carpet of snow and ice. All our weather decks were covered with four feet of snow and our mooring lines had disappeared into the tremendous drifts on the storm lashed pier. At morning coffee-break the chief boatswain mate, who had just returned from an official visit to Wardroom Country, explained the situation to the crew. Two 'T-2' tankers, the SS PENDLETON and the SS FORT MERCER had cracked in half during the last night's blizzard, and the sections were floundering helplessly in the heavy seas. The cutters YAKUTAT and EASTWIND were attempting rescue at the scene. Three more ships were enroute from Boston, and we were now on stand-by. At 1135 hours the District Commander telephoned from Boston and spoke to the O.D., who also happened to be the only officer aboard; as the other officers and also half the crew, were still marooned ashore as a result of the snow storm. The O.D. had no sooner hung up the receiver, when we heard the quartermaster excitedly blurt out the familiar, but always spine-tingling announcement, "Now hear this . . . hear this . . . all hands make preparations for getting underway . . . I say again . . ." All hands scrambled to their assignments as they realized the gravity of this particular rescue mission. The port engine had to be reassembled by the "black gang," the ship made ready for sea by the deck gang, and each missing officer and enlisted man had to be contacted and ordered to return to the ship within the hour . . . no excuses accepted. The captain, like everyone else, had his share of hardship as he returned to his ship. He trudged two miles through the snow drifts from his South Portland home to the inter-ciity bridge, climbed down a piling, and boarded a picket boat from the So. Portland C.G. Base. The small boat then knifed its way through the tormented harbor to the jacobs ladder hanging from the low cutaway taffrail of the ACUSHNET. Captain Joseph was the man we were all glad to see come aboard. Since I had reported last October, he had commanded the ship admirable in several fishing boat rescues off the Grand Banks, and there was a unanimous feeling of trust and confidence, by the crew for our captain, a Coast Guard veteran of 25 years.  At 1430, all hands except one seaman, who had suffered a case of frostbite the night before, and was sent to the Marine Hospital, were aboard and the "mighty A" was ready for sea. The deck crew then manned snow shovels and scrapers and turned-to on the pier in an effort to locate our mooring and storm lines. After twenty minutes of furious digging, we located the bollards, cast off all lines, and officially got under way. I returned topside to inhale a breath of medicinal, fresh sea-air and to view the rugged shoreline of Casco Bay. I knew that it was going to be one of our more rugged trips, as it was already a feat just to maintain a steady upright position, and the ship was still in the channel. As we sped out into open water and came abreast of the Portland Light Ship, anyone who thought that they might get seasick this trip, was, and the others were beginning to think seriously about it. I had only been in the Coast Guard since the previous July. After "boot camp" at Cape May, New Jersey, and two weeks leave in Miami, I reported in to the Boston Base, and was subsequently transferred to Portland, and my new home and training ground-the ACUSHNET. Despite my land-locked ignorance, they were slowly succeeding in transforming me into an acceptable deck hand. After five months of chipping, scraping, and painting any object that remained stationary for more than five minutes, I was presently assigned by the Chief Bo's'n as a mess-cook in the Chief Petty Officer Mess. I had been performing these catering chores for a week now, and the evening meal would be my first serving at sea. After setting the table in accordance with the Fanny Farmer Cook Book, I leaned back against the bulkhead to view my handiwork; only to feel the ship suddenly sink from under my feet, roll fifty degrees to starboard, and clear the table of all place settings, silverware, glasses, and one coffee pyrex. As I was diligently sweeping up the damage, the chief radioman entered, waded through the broken glass and asked, "What happened to supper?" "Nothing has happened to supper yet chief," I explained, "but a minor tragedy has fallen on my supper dishes." "Didn't anybody tell you how to set the table in a rough sea?" "No Sir, that's one thing I must have missed in the Bluejacket's Manual." "Place a damp dishcloth under each dish and glass - and then pray, that's all." I followed his advice, and performed same with instant success; now realizing that the ACUSHNET'S chief petty officers would not have to be fed on paper plates for the remainder of my enlistment.  Photo Courtesy USCG (Official Coast Guard photograph) The ACUSHNET arrived at the scene of the double disaster the next morning at 1100, 55 miles south-southeast or Nantucket Island. Along with the rest of the dazed and sea-sick deck force, I untied the lanyards that had held me safely in the sack through the night, jumped down to the dungaree and debris laden deck where I gaped in awe at the partially submerged bow of the once proud SS FORT MERCER. Five men had been lost to the hungry sea here last night, and the cutter YAKUTAT had just completed the rescue of the remaining survivors, including the tanker's master, by way of rafts and the breeches buoy. There was nothing more to be done here, so we headed north towards the stern section of the FORT MERCER, which had drifted some 25 miles away from her better half. Shortly, the ACUSHNET arrived at the new scene of rescue operations involving the 200 foot stern, which displayed gigantic, jagged slivers of broken steel at her mid-section, and a group of frantic, pleading sailors clutching the rails of her, roller-coasting poop deck. The ice breaker EASTWIND was attempting to retrieve the merchant sailors - one at a time - off the stern by hand-pulling a rubber raft back and forth, but this maneuver was going slowly, and the one rescued survivor had been nearly drowned in the process.  Official USCG Photo; photographer unknown. Our skipper then requested and received permission from the EASTWIND to ease his craft along side the derelict, judging the sixty foot swells with exacting precision, Captain Joseph maneuvered the ACUSHNET alongside the stern section, and in less than a long minute, seven of the merchant seamen leaped to our awaiting arms as we braced ourselves on the ACUSHNET's fantail. Each oncoming wave swept the two vessels closer and closer . . . then the nightmare of the sea exploded in our faces; the two sterns rose up on the same swell and clashed together with the full impetus of the raging ocean. I was knocked down to my knees as the entire ship seemed to drop right out from under my not too steady sea-legs. As the next surging swell gained momentum it looked like it was going to dump the tanker's screw right in the middle of our fantail. I looked up from my fender line in search of someone who would give the order to retreat to safety . . a command was hardly necessary . . . all hands who had been manning equipment on the fantail were fleeing to the ladder that led to the shelter of the boat deck. The captain leaped from the wing into the bridge and jerked the enunciator to"full speed ahead," while screaming to the quartermaster to powerphone the same command to the engine room . . . ON THE DOUBLE! The engines kicked over, groaned and strained, the bulkheads and decks shivered with the sudden, tearing vibration, the double screws churned furiously, and after what seemed an eternity, our ship strained and slowing inched forward, away from the plunging knife-like edges of the tankers propeller. From a safe distance, Captain Joseph surveyed the situation, took three deep breaths, then directed our second approach. The ACUSHNET eased closed to the battered stern, drifted in on the lee side, and came alongside the tanker once again. I returned to the fantail to help eleven more taker crewmen jump to safety. During the operation a hefty merchant sailor leaped onto our slippery taffrail, balanced precariously for a second, then skidded off, but was caught in a last chance reprieve by "Blackie," our sure-handed bo's'n, who leaned over the side and snagged him. The rescued man later explained that the new shoes he wanted to save, and had worn for the leap, had very nearly cost him his life. Another survivor came aboard wearing two suits and two topcoats, but in the chaos had neglected to take along a shirt. As it was, the toll from the double tragedy was five lost from the FORT MERCER's bow and eight more men missing from the bow of the S.S. PENDLETON, which had finally run aground off Chatham, Massachusetts.

Official USCG Photo; ELC 1CGD; photo by Richard C. Kelsey, Chatham, Mass. A Rhode Island seaman, wrapped in government blankets and soused with potent galley coffee, exclaimed, "It was the greatest demonstration of courageous seamanship I've ever seen." It was also the most severe storm he had encountered in twenty years at sea. He wouldn't get an argument from me; my stomach was still practicing half-gainers with a reverse twist. He then described to us how it felt to discover that half of your ship was missing. "I'd been asleep below deck aft for about an hour," he continued in an unsteady voice, "when a violent shock woke me up. It felt as if we'd struck something solid. I could feel the ship shake and start to separate. I stuck my head out the port. The waves were huge, monstrous. They were frightening. I looked down the length of the ship. The midship house near the bow had disappeared. The front end was gone." As darkness filtered in, we were relieved of our duties and directed to return to Boston with our share of the survivors. They were fed, washed, clothed and bedded down in the crew's quarters, where they shook our hands, praised Captain Joseph's seamanship, and in general thanked us for having enlisted in the Coast Guard to help save their lives. It was indeed gratifying to hear from other sea-going men, that they really appreciated us, and knew what the shield on our uniform stood for. As for the commanding officer's commendation, each crew member received, that was o.k., but we were inclined to write our own crew's commendation's, presenting one to the skipper, and one to the big, black, powerful Sea Queen that always took us out there . . . and back. Although almost fifteen years have passed since my ACUSHNET rescue mission, the roar of the anguished sea, and the crunch of ships tossed together, are as vivid in my memory as though they happened yesterday. I was proud to take part in that exciting (fearful at the time) episode, and to this day, I recall those three days as being the most adventurous time of my life.

Editor's Note: Sid Morris served aboard the USCGC Acushnet during the winter of '51-'52 in Portland, Maine. Morris said their biggest adventure came in February, when two tankers split in two off the Mass. coast and they went out to rescue the crew members - which they did by their Capt.'s excellent maneuvering of the ship he noted. Morris, who is retired and living in Miami, Florida, wrote this story about the rescue and it was first published in Sea Classics magazine back around 1965. Morris has granted permission for republication on Sitnews. Morris thought his story would be of interest to the community showing the history and ruggedness of this 213 foot sea-going tug. Morris said the Acushnet was black then and he can't even vision it being pristine white.

|